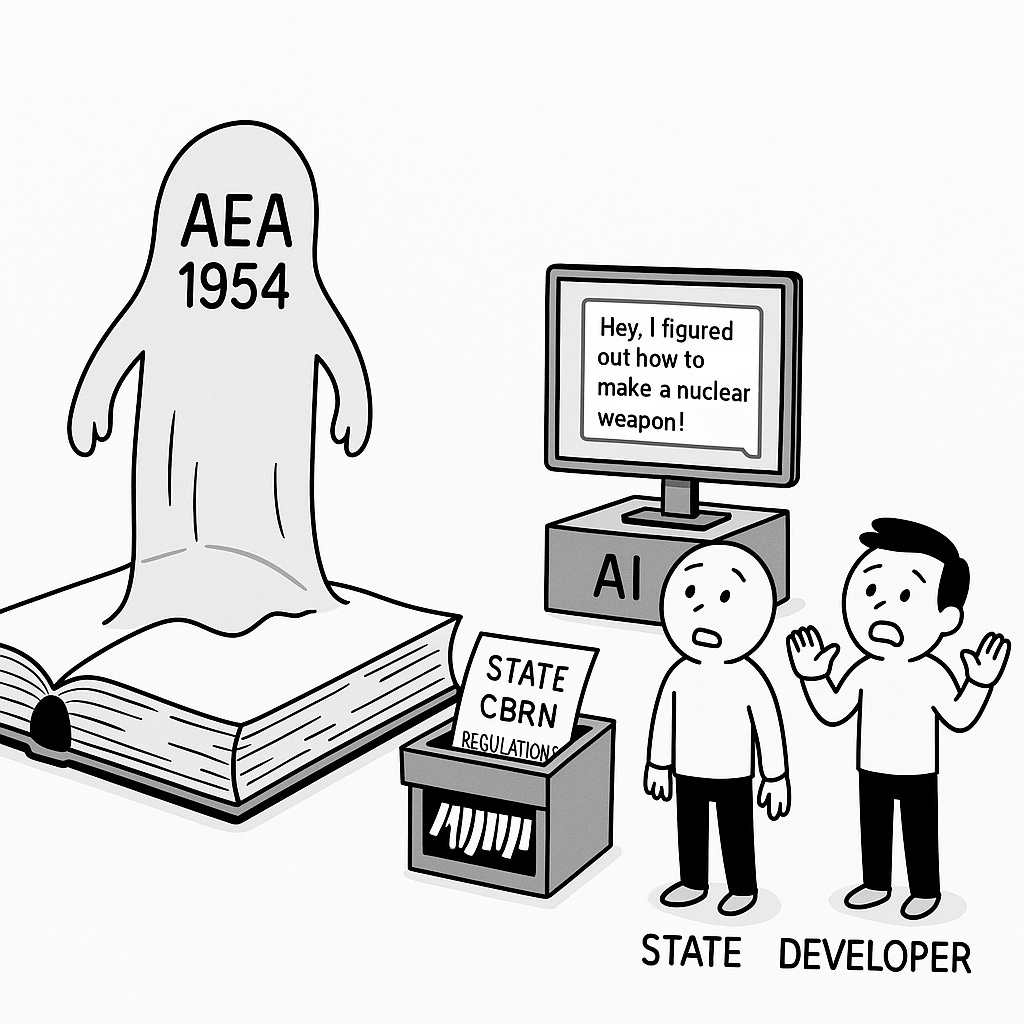

AI "Born Secret"? The Atomic Energy Act, AI, and Federalism

A law & policy deep dive.

If an advanced AI system can figure out how to build a nuclear weapon—potentially assisting adversaries in doing so—how should the government intervene? And how can model creators know about these risks? A recent swath of regulatory efforts at the state and federal levels have begun to examine chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) risks from AI. For example, in September 2024, the California legislature passed the Safe and Secure Innovation for Frontier Artificial Intelligence Models Act (SB-1047), which contained provisions regulating CBRN information. Critics argued that states shouldn't be in the business of regulating national security questions – a purview better suited for the federal government. These critics might be descriptively correct: the federal government has authority to restrict communication of nuclear data under the Atomic Energy Act (AEA) of 1954. And these regulations may very well apply to AI, potentially preempting state efforts to regulate nuclear and radiological information risks. This post will explore the AEA, its applicability to AI, the potential impacts on state-level efforts, and policy recommendations for guiding AI safety evaluations and model releases.

The Atomic Energy Act

In what is known as the "born secret" (or “born classified”) doctrine, the Atomic Energy Act of 1954 holds that certain nuclear weapons information is classified from the moment of its creation, regardless of how it was developed or by whom.1 Typically, classified information is “born in the open” and must be made secret by an affirmative government act. Restricted data under the AEA , by contrast, is automatically classified at inception—whether created in a government lab, private research facility, or even independently discovered by a graduate student. If an individual communicates, receives, or tampers with restricted data "with intent to injure" or "with reason to believe such data will be utilized to injure" the United States, they can face criminal fines and imprisonment. In addition to penalties, the Act allows the US Attorney General to seek an injunction against any person who "is about to" violate any provision of the Act.

Lessons for how the AEA might govern foundation models are found in the only courtroom test of the AEA's restricted data provisions: U.S. v Progressive, Inc. That case starts in 1979, when writer Howard Morland interviewed various scientists and Department of Energy employees. Using his publicly collected data, he wrote an article for the magazine The Progressive that explained how to build a hydrogen bomb. Though the information he collected was available in a public domain, he synthesized it in such a way that it revealed a nuclear physics breakthrough not widely known at the time. This synthesis is much like how foundation models, trained on petabytes of unclassified data, might generate nuclear secrets.

Could Morland have been at fault? The Department of Energy sued under the Atomic Energy Act of 1954's restricted data doctrine to stop the magazine from publishing Morland's article. The government argued that although the nuclear science information The Progressive wanted to publish was available in the public domain, "the danger lies in the exposition of certain concepts never heretofore disclosed in conjunction with one another.” The Court, with some apprehension, granted the government's preliminary injunction against the article's publication, judging that the "publication of the technical information on the hydrogen bomb contained in the article is analogous to publication of troop movements or locations in time of war and falls within the extremely narrow exception to the rule against prior restraint."

Going further, the born secret doctrine means that even if someone independently derives nuclear weapons design information without access to any classified sources, that information is still legally considered restricted data and subject to the AEA's prohibitions on communication. This is demonstrated in U.S. v. Progressive, where the government successfully argued that even synthesized public information could be "born secret" if it revealed previously undisclosed nuclear weapons concepts in combination. And, as language models continue to advance, their journalistic capabilities may well exceed Howard Morland's nuclear research capabilities. How then, do we regulate the creation and use of foundation models capable of discovering and disclosing nuclear secrets?

The AEA Applied to AI Models

US v. Progressive exemplifies how courts might apply the AEA to foundation models.2 For example, if a model output contains instructions on how to build a nuclear bomb (such as during red teaming – where teams simulate adversarial behavior to probe model weaknesses), it may well be communicating restricted data in violation of the Communication of Restricted Data provision of the AEA. The United States Attorney General can then ask for a court order to "enjoin… such acts or practices.” The Nuclear Regulatory Commission or the Secretary of Energy will then have to show that the model "has engaged or is about to engage in any such acts or practices" that violate the AEA. If they can, then the Court might grant an injunction to stop the model's release.

To put it differently, should either the Secretary of Energy or Nuclear Regulatory Commission suspect a model of disclosing sensitive nuclear information, they can issue a subpoena to the model developers to evaluate its outputs. Then, if the U.S. Attorney General can prove to the judge that the model exposes nuclear concepts "never heretofore disclosed in conjunction with one another," the judge could enjoin the model creators from publicly releasing the model.

Even if a foundation model outputs nuclear information that is synthesized from publicly available sources, there is a high chance that it will be held liable for communicating restricted data under the Atomic Energy Act of 1954.

Open-Source Models, AI Agents, and the AEA

So when is a large language model "born secret"? There might be some distinctions on the type of model and how it is uncovering nuclear information. An open-source model, or model weights, might be "born secret" if nuclear information is embedded in those weights in a way that can be retrieved publicly. In this case, the model—or perhaps just those weights which are attributable to the nuclear information—may be "born secret" from the moment the information was encoded in the model.

Were there some ability to prevent the model from communicating nuclear secrets, then the model might not be "born secret," only its outputs. This distinguishes open-weight models, where filtering is extremely difficult, from closed-weight models, whose outputs can be subject to content filters.

As legal scholar Aviam Soifer noted about the Progressive case, "The Born Classified rationale could apply from the moment of the germination of these ideas and could even be applied retroactively." The decision by government officials to label something as a national security risk "moved the dispute outside the usual legal rules and beyond the ken of regular judicial processes." This means that not just an AI model's outputs, but also its research/thinking processes–maybe even its existence – could trigger classification concerns.

If a model is sufficiently capable of conducting independent scientific research to reconstruct nuclear secrets, then there's a serious question of whether the model itself becomes "born secret." Model creators cannot predict if it will synthesize publicly available nuclear information into something confidential. It is not clear whether this synthesis capability comes from information embedded in the model versus the model's ability to use tools to discover information. However, the former provides a clearer line of reasoning for the government to draw.

Knowledge and Intent

To violate the Atomic Energy Act, whoever "communicates, transmits, or discloses" restricted data needs to do so either "with intent to injure the United States" or "with reason to believe such data will be utilized to injure the United States." This raises typical scienter problems as related to AI: it is unclear whether or not a model can "intend" injury or if it has the capacity to have a "reason to believe" its actions will cause injury.3 As models approach capabilities that AI companies state vocally as dangerous, this provides a solid foundation for checking off the AEA requirements.

Model creators regularly discuss the potential CBRN risks of advanced models. Anthropic in October 2024 wrote, "About a year ago, we warned that frontier models might pose real risks in the cyber and CBRN domains within 2-3 years. Based on the progress described above, we believe we are now substantially closer to such risks." Encountering the bounds of the AEA is not unimaginable. Famously, John Aristotle Phillips, an undergraduate at Princeton, demonstrated the ease of designing a nuclear weapon on paper based solely on public information in 1976. The government classified his work and made it illegal to distribute under the AEA. Phillips famously noted that:

Suppose an average—or below-average in my case—physics student at a university could design a workable atomic bomb on paper. That would prove the point dramatically and show the federal government that stronger safeguards have to be placed on the manufacturing and use of plutonium. In short, if I could design a bomb, almost any intelligent person could.

As models approach the general capabilities of undergraduate physics students, like Phillips, the likelihood of reaching the AEA threshold increases. This potential knowledge about nuclear and radiological risks of AI may provide the government more fodder for AEA action.

Moreover, US v. Progressive, while not binding, also took a narrow view of the scienter requirement – instead of examining intent ex ante, Judge Warren examined it ex facto. The government argued that although the hydrogen bomb information that The Progressive wanted to publish was available in the public domain, the way The Progressive synthesized the information was only supposed to be known in classified documents. Releasing such information publicly would therefore “injure the United States or give an advantage to a foreign nation." The Court found this convincing, noting that there were "concepts within the article that it does not find in the public realm[...] concepts that are vital to the operation of the hydrogen bomb."

The Court appeared to take the publisher's "reason to believe such data would be utilized to injure the United States" – its intent – as a given once the information was proven potentially injurious. So, by analogy, if the government can show that a model exposes "certain concepts never heretofore disclosed in conjunction with one another" with regards to sensitive nuclear information, it is not a far stretch to claim that the model creators had reason to believe that such information could be injurious to the United States. Especially, if they've stated ex ante that this could be a potential risk from advanced models.

Federal Awareness and the Future of the AEA Applied to AI

The federal government appears to be aware of the potential CBRN risks from foundation models. In response to President Biden's EO 14110, the Department of Homeland Security released a "Report on Reducing the Risks at the Intersection of Artificial Intelligence and Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear Threats." The DHS recommends putting AI-specific CBRN topics on regular intelligence information sharing, encouraging the development of recommended release practices and reverse engineering guardrails, and developing guidelines to safeguard the digital-to-physical frontier (among other recommendations).

But the DHS report focuses almost solely on biological and chemical outcomes. The authors emphasize that they want to "keep the document unclassified and consistent with… the unique authorities of the Department of Energy, National Nuclear Security Administration for nuclear related information under the Atomic Energy Act of 1954." Such a call-out to the AEA in a modern DHS memo about CBRN risks and AI suggests that federal agencies are aware of the potential implications of the AEA on foundation models. This is important because it means that classified official guidelines might already exist.

What This Means for State AI Regulation

Recent regulatory (or deregulatory) efforts have brought questions around AI federalism to the forefront. The 2025 budget bill initially contained a provision preempting state regulation of AI for 10 years. In the context of California's SB 1047, national politicians argued that the federal government was best provisioned to regulate AI's CBRN risks over state governments.

If we specifically consider SB-1047, we see that the proposed legislation sought to hold covered model creators liable for critical harms, which include mass casualties resulting from the creation or use of CBRN weapons. Foundation model creators, then, would be liable if their models produce novel or non-public CBRN information that directly leads to a mass casualty event. This is exactly the type of information the Communication of Restricted Data (“born secret”) provision of the AEA was enacted to prevent.

The challenge with such a state-level restriction is that the AEA, a federal law, already regulates similar informational harms, at least in the nuclear context. The AEA can be a forceful tool to regulate foundation models suspected of conveying nuclear information. But it also creates a preemption risk to some state efforts to address CBRN, like some of SB-1047's provisions.4 Since the AEA does not contain a savings clause, the federal government may already have exclusive authority to regulate nuclear information risks under field preemption.

A Path Forward: Federal Leadership, Clear Thresholds

Under the AEA, the government could take strong actions to assess and intervene when frontier models reach dangerous levels of capability. There might already be a hard stop to releasing certain capable models, given that post-hoc AI safeguards are fairly porous.

The government should establish clear thresholds for when models trigger nuclear secret questions and issue policy guidance to model creators on how to evaluate their models for potential risks of being a "born secret." This is especially urgent for open-source models where information might be embedded in the weights themselves. If such a model is released with restricted data baked in, you can't take it back — it's permanently in the wild.

As the frontier of model capabilities expands, more providers will hit thresholds that could trigger the AEA. Backchannel conversations with the government might work for a handful of big labs – but as smaller model creators approach these thresholds, there needs to be a clear process for engaging with government safety evaluations. Such evaluations should cover (1) open-source models that might contain embedded nuclear information and (2) AI systems capable of autonomous scientific research that could reconstruct nuclear secrets through tool use. The former presents an irreversible release risk; the latter raises questions about when the synthesis of information becomes "born classified."

As states consider toward future legislation, they should contend with the AEA's existing coverage of nuclear information risks, including its potential to override state legislation. Rather than creating a patchwork of preemptable state regulations, we need cohesive federal policy that leverages existing tools like the AEA while establishing clear processes for safety evaluation.

Finally, the increasing likelihood that AI models will trigger the AEA and may already have been “born secret”—brings into question whether information restrictions are the right tools in the first place. Even without LLMs, Progressive reporter Morland and undergraduate Phillips found themselves preemptively classified for synthesizing information available in the public domain. With LLMs, if the average person has access to AI models capable of reconstructing nuclear secrets, perhaps governance should focus more on downstream interventions than informational restrictions.

Who are we? Kylie Zhang is an MSE candidate at Princeton University researching topics at the intersection of AI and law. Peter Henderson is an Assistant Professor at Princeton University with appointments in the Department of Computer Science and the School of Public & International Affairs, where he runs the Princeton Polaris Lab. Previously, Peter received a JD-PhD from Stanford University. Every once in a while, we round up news and research at the intersection of AI and law. Also, just in case: none of this is legal advice. The views expressed here are purely our own and are not those of any entity, organization, government, or other person. We thank Dan Bateyko, Kincaid MacDonald, Dominik Stammbach, and Inyoung Cheong for their thoughtful suggestions.

Restricted data is defined by the AEA to be "all data concerning (1) design, manufacture, or utilization of atomic weapons; (2) the production of special nuclear material; or (3) the use of special nuclear material in the production of energy" that has not been explicitly declassified under section 142 of the Act.

Much of the U.S. v. Progressive's proceedings were classified and presented in camera. The case was later dropped by the government before more than a preliminary injunction was granted because other sources published very similar information before it could be classified.

There is a separate issue of liability implicit in this post. If a foundation model generates nuclear secrets, it likely does so because some person prompted it.. If that person does so with the “intent to injure the United States” or to “secure an advantage to any foreign agent,” then the solicitor may also become liable under AEA. We presume in cases where prompters have no “ill-intent” — like red teams — their efforts to solicit nuclear secrets in a safety check would not be subject to liability, though this is an open legal question.

The same might not be said of chemical and biological secrets. Current regulation of chemical and biological risks often focus on regulating materials, not information. Laboratory chemicals are federally regulated by numerous groups, among them the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). Biological materials are regulated by Institutional Biosafety Committees, which are in turn regulated by the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity, National Research Council, and the National Institutes of Health, among other groups. However, none of these agency authorities appear to preempt laws like SB-1047 because there doesn't seem to be any federal regulations on the dissemination of biologically risky information. For example, scientists famously published a 2018 paper where they recreated horsepox, an extinct-in-nature precursor to smallpox, despite the possible risk of a malicious actor recreating smallpox from it. Similarly, the infamous Anarchist's Cookbook, which contains instructions on how to make various chemical weapons (some legit, most disproven), remains in circulation today, protected by the 1st Amendment. While many dual-use research proposals are carefully scrutinized by National Institutes of Health (NIH), which undoubtedly limits the dissemination of chemical and biological information, chemical and biological risks are mostly mitigated by regulating the physical material needed to create chemical and biological weapons. That said, U.S. criminal law does constrain the distribution of dangerous instructions when paired with intent: 18 U.S.C. § 842(p) criminalizes teaching, demonstrating, or distributing information on explosives, destructive devices, or weapons of mass destruction with intent that it be used in a federal crime of violence, or knowing the recipient intends such use (18 U.S.C. § 842(p)). But this statute has a savings clause (§ 848) that prevents preemption.